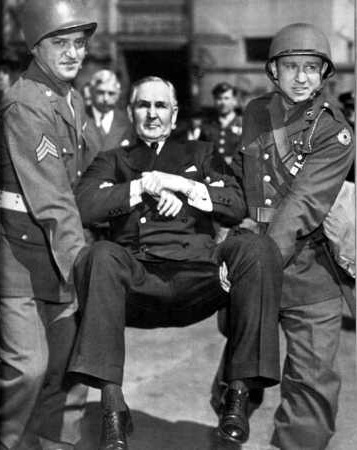

Sewell Avery being taken from his office by National Guardsmen for refusing to settle a strike that endangered delivery of essential goods during World War II

At the end of World War II, Montgomery Ward chairman Sewell Avery made a fateful decision. The United States, he was sure, would experience major difficulties moving from a wartime to a peacetime economy. Millions of troops would return, all seeking jobs. At the same time, factories geared for the production of tanks, bombers, and fighting ships would grind to a halt with no further need for their production.

Avery was not alone in his belief. Many leading economists also predicted that the United States would fall back into the Great Depression. The massive financial stimulus provided by World War II would wear off, and the nation would return to status quo ante.

Let Sears and JCPenney expand; Montgomery Ward would stand pat on its massive cash reserves (one Ward vice president famously said, “Wards is one of the finest banks with a storefront in the US today.”) and when the inevitable collapse came, Montgomery Ward would swallow its rivals at pennies on the dollar.

As we know, it didn’t turn out that way. Instead of falling back into depression, the United States in the postwar years saw unprecedented economic growth.

Sewell Avery was wrong. But was he stupid?

The outcome of the decision doesn’t by itself prove whether the decision was good or bad. Lottery tickets aren’t a good investment strategy. The net return is expected to be negative. On the other hand, occasionally someone wins. That doesn’t make them a genius. Wearing your seatbelt is a good idea. There are, alas, certain rare accidents in which a seatbelt could hamper your escape.

In 1945, no one knew for sure what the postwar world would be like. To understand the future, the only resource we have is the past. It was certainly not unreasonable to conclude that a nation traumatized by depression might well fall back into one.

But it was far from certain.

Year after year the economy grew, but Avery stuck to his guns and refused to permit expansion, expecting the Depression to start any minute now. Sears and JCPenney grew in size and in profits, and by 1954 Montgomery Ward was a lagging also-ran in the department store business. In 2000, the company declared bankruptcy.

Sewell Avery thought ahead, but he failed to think sideways. From our time bound perspective, the future is a wave front consisting of numerous possibilities. We often have only a vague idea of the relative probability of each outcome. But that does not excuse us from the necessity to make decisions.

Foresight is not enough. We must think laterally as well. What if we’re right? What if we’re wrong? What could come out of left field and upset all our precious calculations? What are the signposts that hint at the shape of things to come?

The art of lateral thinking melds classical decision-making with outside the box ideas and a search for clues and models that help us unravel and manage the complexities of organizational life. Whether you are setting strategy for a Fortune 500 corporation or figuring out how your small business plans to cope with economic uncertainty, one answer – whatever it is – simply isn’t good enough.

The art of SideWise thinking – learning to think “what if” – applies numerous models and insights tools to help you avoid the mental blindness and linear thinking that trapped Sewell Avery.